-

Content count

2,756 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

8

Posts posted by Mark Foote

-

-

3 hours ago, Trunk said:

There's a variations of the microcosmic orbit thread in the Daoism section, which comments on, inspired me towards ... this broader topic of "Beginnings".I think that there is a wide variety of aspirants here, with a wide variety of background ... hopefully mostly anectotal (we might touch on classical complete perfection, but I'm not obsessing on it)... and this might vary widely depending on tradition and specific internal path, goal.

When you "started", was there some broad orientation/one piece maybe/method/teaching that you received that was especially helpful? (or, on the other hand, led to trouble?)

... and if you were to give some very short piece of advice, (doesn't have to cover all the bases or anything) for beginning?

I was unsatisfied with my mind, in high school. In my senior year, a friend pointed me to the illustrations of zazen in the back of "The Three Pillars of Zen", by Kapleau, and I started to try to sit cross-legged on the floor for five or ten minutes at a stretch.

A few years later, another friend took me to hear the lectures of a Zen teacher from Japan. Sitting was still very uncomfortable for me after about twenty minutes, but I persevered.

The advice I got from that teacher was "take your time with the lotus". At one point I could sit about 35 minutes in the lotus, did so through a five day sesshin, but now I only sit a sloppy half-lotus, and often only for 25 minutes. Pretty much have sat in the mornings when I first get up, and at night before I go to bed, for all of my adult life now.The sitting has been the teacher, in my life, and I'm grateful every day.

-

4

4

-

1

1

-

-

20 hours ago, idiot_stimpy said:I think movement happens simultaneously with the experience of the unchanging now. Its not separate from it.

Ok, that is actually different from what I said, when I said:

But does the action of the body, and possibly of the mind, proceed from the experience of "just is" without departing the experience?

That's the real test.

You quote Thinley Norbu Rinpoche's commentary on the Ngondro from the treasure texts of Dudjom Lingpa:

So therefore, the pure way of abiding in unconditioned wisdom and the way that appearances manifest are evenly pure. This is called the wisdom of eveness.

He does not say that the way of abiding in unconditioned wisdom and the way that appearances manifest are the same thing, he only says they are evenly pure. That's the distinction I'm trying to make: they are separate, although I don't experience (or I haven't experienced) the complete separation that he seems to describe.

-

1

1

-

-

6 hours ago, stirling said:My post was in reply to Mark, and was specific to it.

I'm honored, but were you responding to:

Let's get SO unpopular!

Or were you responding to:

As (one) dwells in body contemplating body, ardent… that desire to do, that is in body, is abandoned. By the abandoning of desire to do, the Deathless is realized. So with feelings… mind… mental states… that desire to do, that is in mind-states, is abandoned. By the abandoning of the desire to do, the Deathless is realized.

(SN V 182, Pali Text Society V p 159)

I'm guessing you were actually responding to Gautama the Shakyan, and in particular to Gautama's emphasis on a cessation of the desire "to do".

I'm talking about how action can take place in the absence of volition, that to me is the verification part of "practice and verification". You're talking about how the lack of desire results in a particular state of mind, as far as I can tell.

Here's a more modern treatment--notice that there is an action that is taking place, and the emphasis is on the action, even though desire has presumably been abandoned and a wide-open state of mind has presumably been realized:

But usually in counting breathing or following breathing, you feel as if you are doing something, you know– you are following breathing, and you are counting breathing. This is, you know, why counting breathing or following breathing practice is, you know, for us it is some preparation– preparatory practice for shikantaza because for most people it is rather difficult to sit, you know, just to sit.

(“The Background of Shikantaza”; Shunryu Suzuki, Sunday, February 22, 1970, San Francisco; transcript from shunryusuzuki.com)

"Blown out"--necessity in the movement of breath places attention, and the activity of the body follows solely from the location of attention (which is not fixed).

The only good thing Buddhaghosa ever wrote:

The air element that courses through all the limbs and has the characteristic of moving and distending, being founded upon earth, held together by water, and maintained by fire, distends this body. And this body, being distended by the latter kind of air, does not collapse, but stands erect, and being propelled by the other (motile) air, it shows intimation and it flexes and extends and it wriggles the hands and feet, doing so in the postures comprising of walking, standing, sitting and lying down. So this mechanism of elements carries on like a magic trick…

(Buddhaghosa, “Visuddhimagga” XI, 92; tr. Bhikku Nanamoli, Buddhist Publication Society p 360)

-

20 minutes ago, idiot_stimpy said:I think movement happens simultaneously with the experience of the unchanging now. Its not separate from it.

Is that different from what I said? -

23 hours ago, idiot_stimpy said:If it requires any form of effort to see it and maintain it in meditation, it is not it.

Awareness of the totality of the NOW, it 'just is'. The 'just is', always is, effortlessly is, right now. It does not change, although its contents change.

But does the action of the body, and possibly of the mind, proceed from the experience of "just is" without departing the experience?

That's the real test.

-

1

1

-

-

I think about these things a lot... if the cat brings me a rat, I will be sure to place it between my teeth, in hopes that the Jabberwocky will pass go and proceed directly to community chest.

But seriously.

Some voodoo fun from the Zen tradition:

In the Yagyu-ryu (a school of swordsmanship), there is a secret teaching called “Seikosui”. Yagyu Toshinaga, a master of the Yagyu-ryu, taught that it was especially important to concentrate vital energy and power in the front of the body around the navel and at the back of the body in the koshi (pelvic) area when taking a stance. In other words, he means to fill the whole body with spiritual energy. In his “Nikon no Shimei” (“Mission of Japan”), Hida Haramitsu writes:

“The strength of the hara alone is insufficient, the strength of the koshi alone is not sufficient, either. We should balance the power of the hara and the koshi and maintain equilibrium of the seated body by bringing the center of the body’s weight in line with the center of the triangular base of the seated body.”

… we should expand the area ranging from the coccyx to the area right behind the navel in such a way as to push out the lower abdomen, while at the same time contracting the muscles of the anus.

… It may be the least trouble to say as a general precaution that strength should be allowed to come to fullness naturally as one becomes proficient in sitting. We should sit so that our energy increases of itself and brims over instead of putting physical pressure on the lower abdomen by force.

(“An Introduction to Zen Training: A Translation of Sanzen Nyumon”, Omori Sogen, tr. Dogen Hosokawa and Roy Yoshimoto, Tuttle Publishing, pg 59, parentheticals added)

I believe in Gautama's teaching, the "brims over" described above is a feeling that belongs to the second concentration:

… imagine a pool with a spring, but no water-inlet on the east side or the west side or on the north or on the south, and suppose the (rain-) deva supply not proper rains from time to time–cool waters would still well up from that pool, and that pool would be steeped, drenched, filled and suffused with the cold water so that not a drop but would be pervaded by the cold water; in just the same way… (one) steeps (their) body with zest and ease…

(AN III 25-28, Pali Text Society Vol. III p 18-19)

Wait for it...

-

1

1

-

1

1

-

-

2 hours ago, liminal_luke said:Here´s a potentially unpopular opinion. It´s good to develop fluency in both directions -- from manifestation to wuji, and from wuji to manifestion.

It's good to be able to relinquish activity and the identification of self with an actor. Sometimes that might involve reflection on impermanence, and some detachment from the pleasant and unpleasant--maybe even from the neutral of sensation.

(One) makes up one’s mind:

Contemplating impermanence I shall breathe in. Contemplating impermanence I shall breathe out.

Contemplating dispassion I shall breathe in. Contemplating dispassion I shall breathe out.

Contemplating cessation I shall breathe in. Contemplating cessation I shall breathe out.

Contemplating renunciation I shall breathe in. Contemplating renunciation I shall breathe out.

(SN V 312, Pali Text Society Vol V p 275-276; tr. F. L. Woodward; masculine pronouns replaced, re-paragraphed)

I know, I know--get outta here!

-

3

3

-

-

7 hours ago, old3bob said:well said but also and in the meantime someone has to feed the kids, pay the bills, do chores and work some kind of job... thus and only a tiny percentage of folks are or have become renunciates who maintain such a pure state, as for a householder with duties (who granted may sometimes visit such a state) who also try's to live a renunciate's life at the same time will incur bad karma for breaking householder Dharma ...

many of the masters or advanced spiritual folks quoted at this site are renunciates in various ways along with their teachings related to that life, and do not have (or no longer have) spouses, kids, bills, 9-5 jobs, etc. that they have to deal with in the world.

Got an unpopular take on that for you, old3bob (I'm expanding, Apech!).

In the chapter on inbreathing and outbreathing in Samyutta Nikaya V, there's an account of the time Gautama went on retreat for three weeks, and only the monk who brought his food was allowed near him. When he came back from the retreat, he noticed there were fewer monks than when he left. He asked his attendant Ananda about it, and Ananda reminded Gautama that before he left, Gautama had advised the monks to practice the meditation on the unlovely (aspects of the body). Consequently, said Ananda, as many as a score of monks a day had begun "taking the knife".

Gautama had Ananda gather the monks, and he taught them what he said was his own way of living--basically, a particular set of thoughts connected with the four arisings of mindfulness. But get this--that way of living, he said, was "a thing perfect in itself, and a pleasant way of living besides" (no enlightenment necessary).

What I understand from that teaching is that I can knock myself out, looking to turn a corner and be a different person, or I can accept a way of living marked by thoughts initial and sustained, which is something like the way I live now. Well--he observed such thought with the placement of awareness by necessity ("one-pointedness of mind"), and in connection with an inbreath or an outbreath. He did so "most of the time", and "especially in the rainy season"--that's how it was for Gautama.The only thing I really need to master is the ability to arrive at the cessation of habit and volition in the activity of breath, such that I can experience cessation in daily living, when the occasion demands--to master "just sitting", as it were.

I find that the stage of concentration that lends itself to practice in the moment is dependent on the tendency toward the free placement of attention. As I wrote in my last post:

When a presence of mind is retained as the placement of attention shifts, then the natural tendency toward the free placement of attention can draw out thought initial and sustained, and bring on the stages of concentration.

Shunryu Suzuki said:

To enjoy our life– complicated life, difficult life– without ignoring it, and without being caught by it. Without suffer from it. That is actually what will happen to us after you practice zazen.

(“To Actually Practice Selflessness”, August Sesshin Lecture Wednesday, August 6, 1969, San Francisco)

I practice now to experience the free placement of attention as the sole source of activity in the body in the movement of breath, and in my “complicated, difficult” daily life, I look for the mindfulness that allows me to touch on that freedom.

("To Enjoy Our Life")-

1

1

-

-

20 hours ago, stirling said:I guess that isn't my experience, at least with North Americans or practitioners in the UK.

Possibly in disagreement if I understand you correctly (and thus not popular?), but I will say that the single most important thing one could be doing IMHO is recognizing thoughts as thoughts, feelings as feelings, and all simply parts of the story of "self"/I as a mental construction. These are the most obvious things MOST in the way of enlightenment. In realization, the body can be seen at its base level to be a delusion... eventually seen to be the fluxing field of unlabeled sensations it has always been. The way forward in this case is in the simple practice of seeking and resting in stillness.

Quote

“Things grow and grow,But each goes back to its root.

Going back to the root is stillness.

This means returning to what is.

Returning to what is

Means going back to the ordinary.” - Lao Tzu

Let's get SO unpopular!

As (one) dwells in body contemplating body, ardent… that desire to do, that is in body, is abandoned. By the abandoning of desire to do, the Deathless is realized. So with feelings… mind… mental states… that desire to do, that is in mind-states, is abandoned. By the abandoning of the desire to do, the Deathless is realized.

(SN V 182, Pali Text Society V p 159)

-

1

1

-

-

On 3/2/2024 at 9:27 AM, Keith108 said:

Out in the desertKnots on a monks prayer rope

Moved in solitude

Moved in solitude

rocks on the Mojave floor

nice trick to match that

-

2

2

-

-

Let the mind be present without an abode.

(from the Diamond Sutra, translation by Venerable Master Hsing Yun from “The Rabbit’s Horn: A Commentary on the Platform Sutra”, Buddha’s Light Publishing p 60)

-

3

3

-

-

lord love a duck... sorry for the dupe.

-

1

1

-

1

1

-

-

34 minutes ago, Unota said:I guess that was a wrong way to say it. I am interested in it, I'm fascinated by it and I love to read about it. But I will not try to apply it to myself, because I feel like that is not...really my personal...goal? Before I would ever consider something crazy like spiritual development or enlightenment of any sort...Don't I have to learn to love life first? Wouldn't it just be an escape mechanism? How can I do something like that, if I can not be happy with 'going with the flow?' And if I was happy with it, then I think I would never find reason to do spiritual cultivation in the first place. Is it not contradictory?

I, for one, was most unhappy with my mind by my early teens. That's how I came to accept "Focus on body first and let your thoughts take care of themselves" (cited above by Apech as a part of an unpopular opinion).

At seventeen, I learned how to sit zazen from the diagrams at the back of "Three Pillars of Zen". That was reminiscent of the way I initially learned judo, out of a Bruce Tegner book.

When I actually started in at a judo dojo, the principal instructor called his instructing assistants over to witness me demonstrating what I had learned. Years later I found out they were highly amused, although they didn't show it at the time (fortunately. I owe them all a great debt!).My posture will never be exemplary, I'm reconciled to that. And much of what I've learned about internal arts has come out of books, still.

But I agree, there's a love of life, a happiness in living that's natural, a happiness the denial of which is downright unhealthy.

What I found through the seemingly unnatural practice of sitting on the floor with my legs crossed is that the body can place the mind, out of necessity. And understanding that such placement is a natural thing in the rhythm of consciousness, I have mostly reconciled with that same mind that left me so dismayed as a teenager--my mind knows what to do, about one thing.

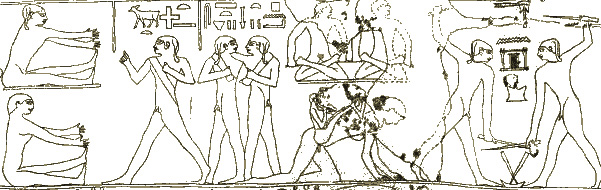

Unnatural to sit a posture that's been around since the Egyptians (you knew I'd get around to it, Apech), or... simply unpopular. You decide...

From the tomb of Ptah-Hotep, 24th century B.C.E.-

1

1

-

1

1

-

-

21 hours ago, kakapo said:http://gnosis.org/naghamm/gosthom.html

"Whoever discovers the interpretation of these sayings will not taste death."

These are the secret words which the Living Jesus spoke and Didymos Judas Thomas wrote. And He said:

Whoever finds the explanation of these words will not taste death.

(The Gospel According to Thomas, coptic text established and translated by A. Guillaumont, H.-CH. Puech, G. Quispel, W. Till and Yassah ‘Abd Al Masih, p. 3 log. 1, ©1959 E. J. Brill)

As (one) dwells in body contemplating body, ardent… that desire to do, that is in body, is abandoned. By the abandoning of desire to do, the Deathless is realized. So with feelings… mind… mental states… that desire to do, that is in mind-states, is abandoned. By the abandoning of the desire to do, the Deathless is realized.

(SN V 182, Pali Text Society V p 159)

"Jesus said to them, "When you make the two into one,When you sit, the cushion sits with you. If you wear glasses, the glasses sit with you. Clothing sits with you. House sits with you. People who are moving around outside all sit with you. They don’t take the sitting posture!

(“Aspects of Sitting Meditation”, “Shikantaza”; Kobun Chino Otogawa; http://www.jikoji.org/intro-aspects/)and when you make the inner like the outer and the outer like the inner,

From my own writing:

... when I realize my physical sense of location in space, and realize it as it occurs from one moment to the next, then I wake up or fall asleep as appropriate.This practice is useful, when I wake up in the middle of the night and need to go back to sleep, or when I want to feel more physically alive in the morning. This practice is also useful when I want to feel my connection to everything around me, because my sense of place registers the contact of my awareness with each thing, as contact occurs.

(Waking Up and Falling Asleep)

and the upper like the lower,

as below, so above: as above, so below...

(Sanyutta-Nikaya, text V 263, Pali Text Society volume 5 pg 235, ©Pali Text Society)

Gautama expanded on this line, saying that one should survey the body upwards from the soles of the feet and downwards from the crown of the head, and comprehend the body as a bag of flesh enclosing impurities.

Ok, now the Dao Bums mini-editor decides to split!

Quoteand when you make male and female into a single one, so that the male will not be male nor the female be female

From my own writing, about the above:

... consciousness of the stretch and activity behind the lower back and in front of the contents of the lower abdomen can become consciousness of stretch and activity behind the sacrum and tailbone and in the vicinity of the genitalia. Such experience is independent of the sex of the individual, and is offered here as a recurrent condition of practice.

(From the Gospel of Thomas)

Quotewhen you make eyes in place of an eye, a hand in place of a hand, a foot in place of a foot, an image in place of an image, then you will enter [the kingdom]."

From my writing:

... These days... I am practicing some kind of scales, as it were. Gautama outlined the feeling of four states, the initial three and then the “purity by the pureness of [one’s] mind”, the fourth. I’ve described that “pureness of mind” as what remains when “doing something” ceases, and I wrote:When “doing something” has ceased, and there is “not one particle of the body” that cannot receive the placement of attention, then the placement of attention is free to shift as necessary in the movement of breath.

The rest of the scales are looking for a grip where attention takes place in the body, as “one-pointedness” turns and engenders a counter-turn (without losing the freedom of movement of attention); finding ligaments that control reciprocal innervation in the lower body and along the spine through relaxation, and calming the stretch of ligaments; and discovering hands, feet, and teeth together with “one-pointedness” (“bite through here”, as Yuanwu advised; “then we can walk together hand in hand”, as Yuanwu’s teacher Wu Tsu advised).

("To Enjoy Our Life")

When there is not one particle of the body that is not pervaded by "purity by the pureness of mind", then there can be "an image in place of an image".

More on the state that proceeds that "purity by the pureness of mind", the state where "you make eyes in place of an eye, a hand in place of a hand, a foot in place of a foot":

Gautama characterized the third state of concentration as follows:

… free from the fervor of zest, (one) enters and abides in the third musing; (one) steeps and drenches and fills and suffuses this body with a zestless ease so that there is not one particle of the body that is not pervaded by this zestless ease. … just as in a pond of blue, white, and red water-lillies, the plants are born in water, grow in water, come not out of the water, but, sunk in the depths, find nourishment, and from tip to root are steeped, drenched, filled and suffused with cold water so that not a part of them is not pervaded by cold water; even so, (one) steeps (one’s) body in zestless ease.

(AN III 25-28, Pali Text Society Vol. III pg 18-19)

In my experience, the base of consciousness can shift to a location that reflects involuntary activity in the limbs and in the jaw and skull. The feeling for activity in the legs, the arms, and the skull is indeed like an awareness of three varieties of one plant grown entirely below a waterline. The experience does have an ease, does require equanimity with regard to the senses, and generally resembles a kind of waking sleep.

Gautama taught that zest ceases in the third concentration, while the feeling of ease continues:

(One) enters & remains in the third (state), of which the Noble Ones declare, ‘Equanimous & mindful, (one) has a pleasant abiding.’

(Samadhanga Sutta, tr. Thanissaro Bhikkhu, AN 5.28 PTS: A iii 25; Pali Text Society, see AN Book of Threes text I,164; Vol II p 147)

That’s a recommendation of the third concentration, especially for long periods. Nevertheless, I find that the stage of concentration that lends itself to practice in the moment is dependent on the tendency toward the free placement of attention. As I wrote in my last post:

When a presence of mind is retained as the placement of attention shifts, then the natural tendency toward the free placement of attention can draw out thought initial and sustained, and bring on the stages of concentration.

... I practice now to experience the free placement of attention as the sole source of activity in the body in the movement of breath, and in my “complicated, difficult” daily life, I look for the mindfulness that allows me to touch on that freedom.

-

On 2/12/2023 at 11:13 PM, iinatti said:

Thanks! I find this an interesting thing to think about, but as Steve says, perhaps spontaneity is the byproduct of practice, not necessarily the objective.This conversation did elicit an interesting thought in me, however. An intention is just a thought--a concept about something you might do in the future. It is no different than any other thought that might arise in consciousness. In my own practice, I am working on avoiding attachments to things, including such thoughts. This is a challenge, and until thinking through this conversation, I have yet to understand why.

Concepts like prajnaparamita and wu wei are a paradox because one cannot eliminate attachments phenomenon by attaching to a phenomenon. One cannot commit to inaction, without acting. One cannot eliminate thoughts by thinking. One cannot intend to act without intentions. These are infinite loop statements, the type that Gödel devised.

There is a subtle workaround, however. If analyzing such an unsolvable statement in a model, they would be avoided altogether by running an iteration and finding a limit. A similar concept can also be applied in practice. One cannot eliminate thoughts by thinking, although one can iteratively reduce or slow thoughts by thinking. One can intend to act less on intentions. One can commit to inaction by acting less. One can reduce attachment to phenomenon while still attaching to the phenomenon of doing so. Might seem like a small distinction, but its a slight change in thinking for me.

Thus, if practicing a meditation and my thoughts are running wild, I do not say to myself "stop thinking," I say to myself "slow down your thinking" That way I can gradually get infinitely close a non thinking state without forcing myself into a paradox.

So, one cannot intend to act spontaneously. One can only intend to be more spontaneous and gradually the spontaneity will take over.

Okay… So, have your hands in the cosmic mudra, palms up, thumbs touching, and there’s this common instruction: place your mind here. Different people interpret this differently. Some people will say this means to place your attention here, meaning to keep your attention on your hands. It’s a way of turning the lens to where you are in space so that you’re not looking out here and out here and out here. It’s the positive version, perhaps, of ‘navel gazing’.

The other way to understand this is to literally place your mind where your hands are–to relocate mind (let’s not say your mind) to your centre of gravity, so that mind is operating from a place other than your brain. Some traditions take this very seriously, this idea of moving your consciousness around the body. I wouldn’t recommend dedicating your life to it, but as an experiment, I recommend trying it, sitting in this posture and trying to feel what it’s like to let your mind, to let the base of your consciousness, move away from your head. One thing you’ll find, or that I have found, at least, is that you can’t will it to happen, because you’re willing it from your head. To the extent that you can do it, it’s an act of letting go–and a fascinating one.

(“No Struggle [Zazen Yojinki, Part 6]”, by Koun Franz, from the “Nyoho Zen” site

https://nyoho.com/2018/09/15/no-struggle-zazen-yojinki-part-6/)Koun Franz referred to a "base of consciousness" that can move away from the head. Gautama spoke of a "one-pointedness of mind" that was synonymous with concentration.

Herein… the (noble) disciple, making self-surrender the object of (their) thought, lays hold of concentration, lays hold of one-pointedness. (The disciple), aloof from sensuality, aloof from evil conditions, enters on the first trance, which is accompanied by thought directed and sustained, which is born of solitude, easeful and zestful, and abides therein.

(SN v 198, Pali Text Society vol V p 174; “noble” substituted for Ariyan)

Gautama spoke of "determinate thought" as action, and of the result of determinate thought as "the activities":

…I say that determinate thought is action. When one determines, one acts by deed, word, or thought.

(AN III 415, Pali Text Society Vol III p 294)

And what are the activities? These are the three activities:–those of deed, speech and mind. These are activities.

(SN II 3, Pali Text Society vol II p 4)

He spoke of the cessation of "action":

And what… is the ceasing of action? That ceasing of action by body, speech, and mind, by which one contacts freedom,–that is called ‘the ceasing of action’.

(SN IV 145, Pali Text Society Vol IV p 85)

When one has attained the first trance, speech has ceased. When one has attained the second trance, thought initial and sustained has ceased. When one has attained the third trance, zest has ceased. When one has attained the fourth trance, inbreathing and outbreathing have ceased… Both perception and feeling have ceased when one has attained the cessation of perception and feeling.

(SN IV 217, Pali Text Society vol IV p 146)

Gautama charted a course to the cessation of "determinate thought" in action, first in the activity of speech, then in the activity of the body in inhalation and exhalation, and finally in the activity of the mind in feeling and perceiving.

Gautama's enlightenment was his insight into the four truths--that came out of "the cessation of feeling and perceiving". No small feat, to experience a cessation of ("determinate thought" in) feeling and perceiving--complete spontaneity of mind--but he also taught a way of living that I believe only relied on regular experience of "the cessation of inhalation and exhalation". Part of that way of living was the experience of thought in connection with an inhalation or an exhalation:

Aware of mind I shall breathe in. Aware of mind I shall breathe out.

(One) makes up one’s mind:

“Gladdening my mind I shall breathe in. Gladdening my mind I shall breathe out.

Composing my mind I shall breathe in. Composing my mind I shall breathe out.

Detaching my mind I shall breathe in. Detaching my mind I shall breathe out.

(SN V 312, Pali Text Society Vol V p 275-276; tr. F. L. Woodward; masculine pronouns replaced)

Much as you said, accepting the activity of the mind, with a positivity that allows for detachment.

-

1

1

-

-

Thought this might be of interest to other 'bums:

"The contents of Topic 86 provide evidential support for an interpretation of Mencius as advocating internalist belief in the innate potential for goodness in human nature. This engages Mencius’s discussion at 3B9 in which he attacks the doctrines of Yáng Zhu¯ 楊朱 and Mò Dí 墨翟, who advocate egoism and altruism, respectively. Mencian Confucianism repudiates these act-based ethics in favor of the cultivation of character (Csikszentmihalyi 2002). This is uncontroversial, but it leads to an ongoing interpretive problem about self-cultivation. Consider Mencius’s four “sprouts” of virtues (sì dua¯n 四端) in 2A6, where he writes that “if one is without the heart (xı¯n 心) of compassion, one is not human.… The feeling of compassion is the sprout of benevolence” (Van Norden 2008, 46; see also the archer analogy at 2A7). On one interpretation of these passages, the cultivation of feelings appears to be the source of moral virtue in Mencius, making Mencius representative of what is known in philosophy as an “internalist” theory of moral motivation. This allegedly contrasts with moral motivation and cultivation as found in Analects and Xunzi. These two texts are thought to advocate a greater number of, and greater roles for, externalist sources of morality like ritual (lıˇ 禮), patterned civility (wén), and rectification of names (zhèngmíng 正名). Our evidence appears to support this interpretation of Mencius. We draw additional evidence for this interpretation from several sources in traditional scholarship. For example, Slingerland (2003) argues that Mencius is uniquely and distinctively “internalist,” and Kline (2000) that Mencius’s ethics are “inside-out,” as have others (Ihara 1991; Wong 1991). However, since Topic 86 has a high text weight in only Discourses on salt and iron, and not in our core Confucian texts, we must collect additional evidence for the internalist interpretation of Mencius before we can rest confident that it is correct."

(p 20)https://static1.squarespace.com/static/56b23f391bbee0832a71e819/t/5f7904c5c8f18a2d0326c669/1601766610059/Nichols%2C+et+al.+2017+JAS+Chinese+Philosophy+Machine-Learning.pdf240311-Nichols,+et+al.+2017+JAS+Chinese+Philosophy+Machine-Learning.pdf

-

5 hours ago, Master Logray said:If Jesus never demonstrated anything special, would Christianity even exist with his teachings alone?

The Gospel of Thomas is without question the most significant book discovered in the Nag Hammadi library. Unlike the Gospel of Peter, discovered sixty years earlier, this book is completely preserved. It has no narrative at all, no stories about anything that Jesus did, no references to his death and resurrection. The Gospel of Thomas is a collection of 114 sayings of Jesus.

... The Jesus of this Gospel is not the Jewish messiah that we have seen in other Gospels, not the miracle-working Son of God, not the crucified and resurrected Lord, and not the Son of Man who will return on the clouds of heaven. He is the eternal Jesus whose words bring salvation.Many of the sayings of Jesus in this Gospel will be familiar to those who have read the Synoptic Gospels... Other sayings sound vaguely familiar, yet somewhat peculiar: “Let him who seeks not cease seeking until he finds, and when he finds, he will be troubled, and when he is troubled, he will marvel, and he will rule over the All”.

(https://ehrmanblog.org/the-gospel-of-thomas-an-overview/#)

In the first century of the Common Era, there appeared at the eastern end of the Mediterranean a remarkable religious leader who thaught the worship of one true God and declared that religion meant not the sacrifice of beasts but the practice of charity and piety and the shunning of hatred and enmity. He was said to have worked miracles of goodness, casting out demons, healing the sick, raising the dead. His exemplary life led some of his followers to claim he was a son of God, though he called himself the son of man. Accused of sedition against Rome, he was arrested. After his death, his disciples claimed he had risen from the dead, appeared to them alive, and then ascended to heaven. Who was this teacher and wonder-worker? His name was Apollonius of Tyana; he died about 98 A.D., and his story may be read in Flavius Philostratus's "Life of Apollonius".

(Randel Helms, "Gospel Fictions", p 9)Maybe someone here will know better than me, but doesn't the practice of a practicing Christian owe more to Paul than to Jesus?

-

On 3/6/2024 at 12:22 PM, idiot_stimpy said:How does one at a glance see energy and upper mental bodies? Is this some type of ESP almost everyone does not have?

-

1

1

-

-

1 hour ago, Celestial Fox Beast said:If I see those things in my normal state, I would also think that I have a problem (a serious one), all that I describe happens after opening the mysterious path, which, in my humble interpretation (may be wrong) is self induced sleep paralysis, but in a way that you are not bound to material mind and its illusions. This state is known for its hypnagogic and hypnopompic hallucinations, very vivid and intense, and I also have a foot on pure skepticism and modern science that, what I do, is just playing with my brain.

I honestly don't believe that after seeing and experimenting some phenomena, but I MUST contemplate the possibility, because letting both foots into magic thinking is just dangerous.

Let me confess, I've only ever read a few passages from GF.

I played with hypnosis a lot as a teenager, both with hypnotizing others and with autohypnosis.I met a Zen teacher in the early '70's, listened to a few of his lectures but never tried to be a formal student. By then I was sitting half-lotus for at least short intervals daily, but the period length at the local Zen Center where I went for the lectures was 40 minutes, so I started aiming for that.

In the '80's, that same Zen teacher closed a lecture at S. F. Zen Center by saying: "You know, sometimes zazen gets up and walks around." I had exactly that experience in 1975, in a room off the Golden Gate Park panhandle in San Francisco--I'm guessing it was partly from exposure to the Zen teacher, just like when I took judo and everybody in the dojo picked up the master teacher's favorite throw. Kind of an osmosis thing.The difficulty was in integrating that experience back into my daily life.

Now when I sit down on the cushion, I open myself to a particular experience:

The presence of mind can utilize the location of attention to maintain the balance of the body and coordinate activity in the movement of breath, without a particularly conscious effort to do so. There can also come a moment when the movement of breath necessitates the placement of attention at a certain location in the body, or at a series of locations, with the ability to remain awake as the location of attention shifts retained through the exercise of presence.

That necessity is not simply the necessity for breath:

There’s a frailty in the structure of the lower spine, and the movement of breath can place the point of awareness in such a fashion as to engage a mechanism of support for the spine, often in stages.

I believe the location of attention that shifts and moves is what Mencius described as the "heart-mind"--I believe it was Mencius who said, "seek the release of the heart-mind". I would put that another way:

When “doing something” has ceased, and there is “not one particle of the body” that cannot receive the placement of attention, then the placement of attention is free to shift as necessary in the movement of breath.

When a presence of mind is retained as the placement of attention shifts, then the natural tendency toward the free placement of attention can draw out thought initial and sustained, and bring on the stages of concentration:

… there is no need to depend on teaching. But the most important thing is to practice and realize our true nature… [laughs]. This is, you know, Zen.

(Shunryu Suzuki, Tassajara 68-07-24 transcript from shunryusuzuki.com)

(Shunryu Suzuki on Shikantaza and the Theravadin Stages)

The experience of the heart-mind, of the mind that moves, is in a sense "other-worldly"--action proceeds from the location of the heart-mind, and not by will or volition.The difficulty is that most people will lose consciousness before they cede activity to the location of attention–they lose the presence of mind with the placement of attention, because they can’t believe that action in the body is possible without “doing something”...

(ibid)

Quote

Sometimes when you are back from those practices, for a couple of minutes, you can see things that are coincident with other people that also practice spiritual meditations, last time, I see a sort of translucid spider on the wall... I get closer and I notice that the crature was a sort of bag full of eggs with spider legs... and then it fade away. I also have seen black strings suspended in the air, bulbs on corners and... generally ugly thingys inside houses. Of course, only for a brief time after ending a practice, and not always...

Sounds like scopolamine. -

16 hours ago, S:C said:

Sorry for the derailing: where is this from and what does it mean?

As to what it means: you could do worse, than to read my PDF A Natural Mindfulness. Not by much, but you could.I'll try for the Reader's Digest version.

Gautama spoke of laying hold of “one-pointedness” in the induction of the first “trance”:

Herein… the (noble) disciple, making self-surrender the object of (their) thought, lays hold of concentration, lays hold of one-pointedness. (The disciple), aloof from sensuality, aloof from evil conditions, enters on the first trance, which is accompanied by thought directed and sustained, which is born of solitude, easeful and zestful, and abides therein.

(SN V 198, Pali Text Society vol V p 174; “noble” substituted for Ariyan)

I have described the experience of “one-pointedness of mind” as something that can occur in the movement of breath:

The presence of mind can utilize the location of attention to maintain the balance of the body and coordinate activity in the movement of breath, without a particularly conscious effort to do so. There can also come a moment when the movement of breath necessitates the placement of attention at a certain location in the body, or at a series of locations, with the ability to remain awake as the location of attention shifts retained through the exercise of presence.

In my experience, the “placement of attention” by the movement of breath only occurs freely in what Gautama described as “the fourth musing”:

Again, a (person), putting away ease… enters and abides in the fourth musing; seated, (one) suffuses (one’s) body with purity by the pureness of (one’s) mind so that there is not one particle of the body that is not pervaded with purity by the pureness of (one’s) mind.

(AN III 25-28, Pali Text Society Vol. III p 18-19, see also MN III 92-93)

The “pureness of mind” refers to the absence of any intention to act. Suffusing the body with “purity by the pureness of (one’s) mind” is widening awareness so that there is “not one particle of the body” that cannot become the location where attention is placed.

Gautama's description of the feeling of the "third musing" went as follows:… free from the fervor of zest, (one) enters and abides in the third musing; (one) steeps and drenches and fills and suffuses this body with a zestless ease so that there is not one particle of the body that is not pervaded by this zestless ease. … just as in a pond of blue, white, and red water-lillies, the plants are born in water, grow in water, come not out of the water, but, sunk in the depths, find nourishment, and from tip to root are steeped, drenched, filled and suffused with cold water so that not a part of them is not pervaded by cold water; even so, (one) steeps (one’s) body in zestless ease.

(AN III 25-28, Pali Text Society Vol. III p 18-19, see also MN III 92-93, PTS p 132-134)

I wrote:

In my experience, the base of consciousness (the placement of attention) can shift to a location that reflects involuntary activity in the limbs and in the jaw and skull. The feeling for activity in the legs, the arms, and the skull is indeed like an awareness of three varieties of one plant grown entirely below a waterline. The experience does have an ease, does require equanimity with regard to the senses, and generally resembles a kind of waking sleep.

(The Early Record, parenthetical added)

About that "ease":

Gautama spoke of suffusing the body with “zest and ease” in the first concentration:

“… (a person) steeps, drenches, fills, and suffuses this body with zest and ease, born of solitude, so that there is not one particle of the body that is not pervaded by this lone-born zest and ease.”

(AN III 25-28, Pali Text Society Vol. III p 18-19, see also MN III 92-93, PTS p 132-134)

Words like “steeps” and “drenches” convey a sense of gravity, while the phrase “not one particle of the body that is not pervaded” speaks to the “one-pointedness” of attention, even as the body is suffused.

If I can find a way to experience gravity in the placement of attention as the source of activity in my posture, and particular ligaments as the source of the reciprocity in that activity, then I have an ease.

The striking thing to me about my experience on the cushion these days is that I am practicing some kind of scales, as it were. Gautama outlined the feeling of four states, the initial three and then the “purity by the pureness of [one’s] mind”, the fourth. I’ve described that “pureness of mind” as what remains when “doing something” ceases, and I wrote:

When “doing something” has ceased, and there is “not one particle of the body” that cannot receive the placement of attention, then the placement of attention is free to shift as necessary in the movement of breath.

The rest of the scales are looking for a grip where attention takes place in the body, as “one-pointedness” turns and engenders a counter-turn (without losing the freedom of movement of attention); finding ligaments that control reciprocal innervation in the lower body and along the spine through relaxation, and calming the stretch of ligaments; and discovering hands, feet, and teeth together with “one-pointedness” (“bite through here”, as Yuanwu advised; “then we can walk together hand in hand”, as Yuanwu’s teacher Wu Tsu advised).

-

1

1

-

-

16 hours ago, S:C said:Quotebite through here”, as Yuanwu advised; “then we can walk together hand in hand”, as Yuanwu’s teacher Wu Tsu advised).

Sorry for the derailing: where is this from and what does it mean?

As to "where it's from".You must strive with all your might to bite through here and cut off conditioned habits of mind. Be like a person who has died the great death: after your breath is cut off, then you come back to life. Only then do you realize that it is as open as empty space. Only then do you reach the point where your feet are walking on the ground of reality.

("Zen Letters: Teachings of Yuanwu", translated by J.C. and Thomas Cleary, p 84)

Wikipedia: "Yuanwu Keqin (1063–1135) was a Han Chinese Chan monk who compiled the Blue Cliff Record."

The "Blue Cliff Record" is a famous compendium of Zen "cases".

The quote from Wu Tsu, I took from Yuanwu's commentary on a case in the "Blue Cliff Record":‘Hsueh Feng taught the assembly saying, “On South Mountain there’s a turtle-nosed snake. All of you people must take a good look.”’

… When Hsueh Feng speaks this way, ‘On South Mountain there’s a turtle-nosed snake,’ tell me, where is it?

... My late teacher Wu Tsu said, “With this turtle-nosed snake, you must have the ability not to get your hands or legs bitten. Hold him tight by the back of the neck with one quick grab. Then you can join hands and walk along with me.”

(The Blue Cliff Record, tr. Cleary Cleary, “Twenty-second Case: Hsueh Feng’s Turtle-Nosed Snake”, p 144, 151)

Regarding "one quick grab", I wrote:

I’m bound to be bitten by Wu Tsu, if I take his advice to mean there’s something I should do. It’s about realizing a cessation of “doing”, but I think I might run into him, in the stretch of ligaments.

(Common Ground) -

On 3/7/2024 at 1:06 PM, S:C said:@Mark Foote, I am sorry, that there was a scam on the site, - I hadn't visited it, and I don't use google chrome. I'm glad you find a better sense of timing through meditation, however I get confused about the difference of 'the cessation of doing' and 'the cessation of breath' (which is not a thing one should get confused about) and I admire your dedication to the classical writings.

S:C, you had nothing to do with that site, it was simply the first thing presented in the search results. Odd that Google doesn't recognize that clicking on that link will give a Google warning, and place that site a lot further down in the search results.

Can I say that I admire you responding to everybody's two cents, as you did there. Makes us all feel appreciated, whether we deserve to feel that way or not...

About the cessation of "doing something". Shunryu Suzuki said:

But usually in counting breathing or following breathing, you feel as if you are doing something, you know– you are following breathing, and you are counting breathing. This is, you know, why counting breathing or following breathing practice is, you know, for us it is some preparation– preparatory practice for shikantaza because for most people it is rather difficult to sit, you know, just to sit.

(“The Background of Shikantaza”; Shunryu Suzuki, Sunday, February 22, 1970, San Francisco; transcript from shunryusuzuki.com)

Regarding the difference between "the cessation of doing" and "the cessation of breath"--keep in mind that Gautama defined "action", or "the activities", in terms of "determinate thought":

…I say that determinate thought is action. When one determines, one acts by deed, word, or thought.

(AN III 415, Pali Text Society Vol III p 294)

And what are the activities? These are the three activities:–those of deed, speech and mind. These are activities.

(SN II 3, Pali Text Society vol II p 4)

And what… is the ceasing of action? That ceasing of action by body, speech, and mind, by which one contacts freedom,–that is called ‘the ceasing of action’.

(SN IV 145, Pali Text Society Vol IV p 85)

…I have seen that the ceasing of the activities is gradual. When one has attained the first trance, speech has ceased. When one has attained the second trance, thought initial and sustained has ceased. When one has attained the third trance, zest has ceased. When one has attained the fourth trance, inbreathing and outbreathing have ceased… Both perception and feeling have ceased when one has attained the cessation of perception and feeling.

(SN IV 217, Pali Text Society vol IV p 146)

The meaning of "inbreathing and outbreathing have ceased" can therefore be read: "(determinate thoughts in) inbreathing and outbreathing have ceased". Not that the breathing has ceased, but that "doing something" with regard to the activity of the body in inhaling and exhaling has ceased.

Moshe Feldenkrais spoke of upright posture in which both "doing something" through the exercise of volition and "doing something" simply by virtue of habit have ceased:…good upright posture is that from which a minimum muscular effort will move the body with equal ease in any desired direction. This means that in the upright position there must be no muscular effort deriving from voluntary control, regardless of whether this effort is known and deliberate or concealed from the consciousness by habit.

(“Awareness Through Movement”, Moshe Feldenkrais, p 76, 78)

What Gautama taught was a way to sit down and arrive at the cessation of "doing something" with regard to the activity of the body in inhalation and exhalation. Suzuki referred to that as "just sitting", or shikantaza. Gautama further taught a way of living that involved regular experience of the cessation of "doing something" in daily life--he described that way of living as "something perfect in itself, and a pleasant way of living, besides."

Gautama also taught that there are states of concentration that lead to the cessation of "doing something" with regard to actions of feeling and perceiving (that's mentioned in the quote above, about the gradual ceasing of the activities). That would be the ceasing of "determinate thought" in feeling and perceiving, the cessation of habit and volition in activity of the mind. That's the attainment associated with Gautama's enlightenment, his insight into the four truths. -

On 3/6/2024 at 1:03 PM, Bindi said:Quote

What a profound dream!

I follow a progression like this in my sitting, for awhile now. I drive, I'm at a tree with a trunk, there's a man and woman in the active and receptive aspects of my effort, there's a taste of action by virtue of the placement of attention rather than volition, then there's no trunk but just a recognition of something that I have already partaken of.

Interesting, is this a scenario you have consciously created or did the scene just happen?

I'm just relating the symbols in your dream to my experience in sitting.

The fruit that drops on the table--a one-pointedness of mind that can shift location and a sense of gravity that pervades the body are the fruit and the table to me. There's no eating the fruit.

The striking thing to me about my experience on the cushion these days is that I am practicing some kind of scales, as it were. Gautama outlined the feeling of four states, the initial three and then the “purity by the pureness of [one’s] mind”, the fourth. I’ve described that “pureness of mind” as what remains when “doing something” ceases, and I wrote:

When “doing something” has ceased, and there is “not one particle of the body” that cannot receive the placement of attention, then the placement of attention is free to shift as necessary in the movement of breath.

The rest of the scales are looking for a grip where attention takes place in the body, as “one-pointedness” turns and engenders a counter-turn (without losing the freedom of movement of attention); finding ligaments that control reciprocal innervation in the lower body and along the spine through relaxation, and calming the stretch of ligaments; and discovering hands, feet, and teeth together with “one-pointedness” (“bite through here”, as Yuanwu advised; “then we can walk together hand in hand”, as Yuanwu’s teacher Wu Tsu advised).

In the months since I wrote my friend, I’ve had some time to reflect. There are some things I would add, on my practice of “scales”.

Gautama spoke of suffusing the body with “zest and ease” in the first concentration:

“… (a person) steeps, drenches, fills, and suffuses this body with zest and ease, born of solitude, so that there is not one particle of the body that is not pervaded by this lone-born zest and ease.”

(AN III 25-28, Pali Text Society Vol. III p 18-19, see also MN III 92-93, PTS p 132-134)

Words like “steeps” and “drenches” convey a sense of gravity, while the phrase “not one particle of the body that is not pervaded” speaks to the “one-pointedness” of attention, even as the body is suffused.

If I can find a way to experience gravity in the placement of attention as the source of activity in my posture, and particular ligaments as the source of the reciprocity in that activity, then I have an ease.

-

1

1

-

-

On 3/7/2024 at 7:25 AM, thelerner said:Has it done anything great for me? Don't know, maybe I'd be even worse without it. For me, it's a pleasant way to sit and drop my mind.

Puts me in mind of a song:

Relax your mind, relax your mind

Make you feel so fine sometime

Sometime you got to relax your mind

When the light turns green

Put your foot down on the gasoline

Sometime you got to relax your mind

When the light turns red

Put your foot down on the brake instead

Sometime you got to relax your mind

When the light turns blue

What in the world are you gonna do

Sometime you got to GF your mind(Jim Kweskin, with slight alteration)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=963_5AiDk94

-

1

1

-

"Beginnings" - first (mis-)steps n' (dis)orientation on the path

in General Discussion

Posted · Edited by Mark Foote

Took me a lot of years, of always having it in mind and sitting mostly half-lotus.

Dennis Merkel, Zen teacher who at one point in time was associated with the L. A. Zen Center, says he sat half-lotus for a couple of decades, then full-lotus for a couple, and now Burmese for a decade or so (ankles on the ground, one leg in front of the others). He has transmission in both the Rinzai and Soto traditions, if I understand correctly.

I should confess, when I did that five-day sesshin at Jikoji Zen Center, they pretty much alternated 40- and 30- minute sittings, and I had to uncork my lotus at about 35 minutes every time on the 40 minute sittings. Very embarassing, but I was determined not to hurt my knees, and I consistently felt something in my knees at about 35 minutes.

Last I heard, the periods at L. A. Zen Center sesshins are 35 minutes, except for one initial 50 minute sitting--guess I'm not the only one.

Maybe a couple of years after that five-day sesshin, I began to feel something in my knees when I was out walking, and I decided to forget about the lotus and 40-minutes and just go with a sloppy half-lotus for 25 minutes. My knees returned to normal.

Lately I sit beyond 25 minutes a lot, in the half-lotus (or Burmese, if my ankle falls off the opposite calf, as it seems to do with the right leg up). Seems like I have to finish the time I feel is mandatory, before I can "just sit".

But my sitting has changed. I have a better idea, how to turn over the reins:

The presence of mind can utilize the location of attention to maintain the balance of the body and coordinate activity in the movement of breath, without a particularly conscious effort to do so. There can also come a moment when the movement of breath necessitates the placement of attention at a certain location in the body, or at a series of locations, with the ability to remain awake as the location of attention shifts retained through the exercise of presence.

There’s a frailty in the structure of the lower spine, and the movement of breath can place the point of awareness in such a fashion as to engage a mechanism of support for the spine, often in stages.

I don't know what Apech means by "look at your mind", but that's what I'm doing--looking at the location of my awareness, instead of the contents.

When “doing something” has ceased, and there is “not one particle of the body” that cannot receive the placement of attention, then the placement of attention is free to shift as necessary in the movement of breath.

The difficulty is that most people will lose consciousness before they cede activity to the location of attention–they lose the presence of mind with the placement of attention, because they can’t believe that action in the body is possible without “doing something”.

Turn it around, let the "where" not the "who" act past 20 minutes or so (sooner if you can), and your knees will thank you.

Issho Fujita, demonstrating a relationship between "one-pointedness of mind" and the activity of the body in inhalation and exhalation in zazen:

Shunryu Suzuki, describing to his students how they could avoid pain in their legs in sitting:

If you are going to fall, you know, from, for instance, from the tree to the ground, the moment you, you know, leave the branch you lose your function of the body. But if you don’t, you know, there is a pretty long time before you reach to the ground. And there may be some branch, you know. So you can catch the branch or you can do something. But because you lose function of your body, you know [laughs], before you reach to the ground, you may lose your conscious[ness].

(“To Actually Practice Selflessness”, Shunryu Suzuki; August Sesshin Lecture; San Francisco, August 6, 1969)

Dogen:

When you find your place where you are, practice occurs, actualizing the fundamental point.

("Genjo Koan", tr Tanahashi)

The "where", as the source of the activity of the body from outbreath to inbreath, and from inbreath to outbreath:

When you find your way at this moment, practice occurs, actualizing the fundamental point…

(ibid)

... the Blessed One addressed the monks. "Whoever develops mindfulness of death, thinking, 'O, that I might live for a day & night... for a day... for the interval that it takes to eat a meal... for the interval that it takes to swallow having chewed up four morsels of food, that I might attend to the Blessed One's instructions. I would have accomplished a great deal' — they are said to dwell heedlessly. They develop mindfulness of death slowly for the sake of ending the effluents.

"But whoever develops mindfulness of death, thinking, 'O, that I might live for the interval that it takes to swallow having chewed up one morsel of food... for the interval that it takes to breathe out after breathing in, or to breathe in after breathing out, that I might attend to the Blessed One's instructions. I would have accomplished a great deal' — they are said to dwell heedfully. They develop mindfulness of death acutely for the sake of ending the effluents.

(AN 6.19 PTS: A iii 303; Maranassati Sutta: Mindfulness of Death (1) tr Thanissaro Bhikkhu)